I just rediscovered the digitized microforms of the Revolutionary War pension files (pensions granted from 1832 onward) available from ‘HeritageQuest’ via many subscription libraries (including the Boston Public Library, for Massachusetts Residents, and many other public libraries throughout the US). By my count my children have 39 ancestors listed in the DAR Patriot Index, of whom 28 apparently saw military service (almost all in local militias, not Continental Army units). [I have 16, of whom 11 saw military service; my wife has 23, of whom 17 saw military service. She has all the militia officers too — a couple of captains and three lieutenants. See our revolutionary ancestors marked in these four charts, one for each of my parents, and one for each of her parents: MHT, EDT, JRS, PLF.]

Of these 28 military men, six are represented by applications under the 1832 federal pension program, either for themselves or by their widows. Of these six pension applications, four were rejected! The six are (with file numbers):

Andrew Griffin (1758-1829) of Gloucester, Massachusetts — R4316

Willey Hill (1759-1849) of Lee, New Hampshire — R5015

Caleb Lane (1759-1850), of Gloucester — S29961

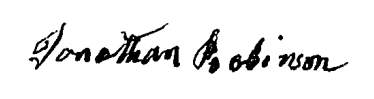

Jonathan Robinson (1760-1843) of Gloucester — S30072

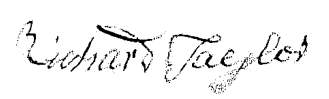

Richard Taylor (1760-1843) of Frederick Co., Virginia and Ohio Co., Kentucky — R10425

John Wingfield, Jr. (1761-1802) of Hanover Co., Virginia and Wilkes Co., Georgia — R11715

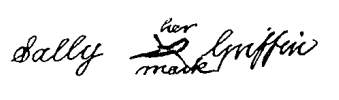

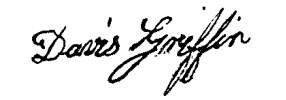

[These six are here shown with their signatures from the digitized applications, except for Andrew Griffin, represented by his widow Sally and son Davis (also my ancestor); and John Wingfield, represented by his widow Mary, who survived him by 43 years. Unfortunately on Richard Taylor’s file the pages are so dark, heavily stippled and low-contrast as to render his signature invisible in places.]

Of these six only Lane and Robinson (who were long-acquainted neighbors and had served together, and testified on each other’s behalf) actually got pensions. The others — with ‘R’ in front of their file numbers — were rejected. Obviously six files is a tiny sample, but what percentage of all extant federal petition applications were rejected? The basis for rejection is apparently not stated outright in the file. Two of the four are found in the 1852 printed index of rejected pension applications, which lists a brief reason for rejection. Willey Hill, a fifer, was noted there not to have served the requisite six months. Richard Taylor’s entry is annotated “service not properly set forth, or estimated or proved;” this is presumably the largest category for rejected application, meaning simply that there was not sufficient proof furnished for satisfaction of the pension administrators. I wonder whether the threshold of proof may have varied from place to place. Of the two others, a twentieth-century typewritten letter (to an apparent descendant) in the Wingfield file notes that “the claim was not allowed as she [i.e. Wingfield’s widow] failed to establish satisfactory proof of service as alleged.” The final rejected application, Andrew Griffin’s, sought a pension, then retroactive pension arrears, for his widow Sally under the 1832 act (she died in 1840). Nothing came of that, presumably for lack of proof of service.

Now, how far does rejection of a pension application impugn the claimed service? For our purposes, from a greater historical distance, perhaps we are more ready to credit claims of service in pension applications—where the claimant is the one who actually was supposed to have served—than, say, the vague and often confused assertions of descendants based on family traditions. I’m not aware of how the lineage societies treat pension application depositions.

In the Willey Hill case, it is interesting that Hill’s affadavit claims well over a year of service (including reenlistments), while the annotation in the 1852 index states tersely that less than six months was proved. Richard Taylor’s file in the 1852 index has a terse statement that the “service was not properly set forth, or estimated or proved.” This file, which I also inspected on microfilm at a NARA repository some years ago, has interesting additional documents not included in the HeritageQuest digitization. In the microfilmed file, there is an exchange of letters, dated December 1842, between Taylor’s Federal congressman, Representative Phillip Triplett, and the Pension Office. In response to Rep. Triplett’s testimonial for Taylor and inquiry as to status, the pension officer wrote,

He alleges 2 terms of militia which he estimates at 6 & 8 months. In this he must be wholly mistaken. There were no such terms in the militia & the utmost of a tour was but six months. But no evidence whatever is adduced of either term. If his chances of obtaining proof have been diminished by the lapse of time, he has himself by delay contributed to the difficulty. The numerous claimants in Va for militia service under the Act must have furnished “abundant means of proving any service actually rendered,” if he had sought them in time.

In fact, in this case, the surviving diary of his militia captain shows that his entire county militia company ended up being attached to a Continental Line regiment during the campaign leading up to the siege of Yorktown, and was in the field for a period more or less matching Taylor’s statement. But from a procedural point the interest is that the file contains more information than what was digitized by HeritageQuest; these additional papers also offer insight into the workings of the Pension Office. Procedurally these rejected pension applications might be more interesting than their accepted counterparts.

Post a Comment