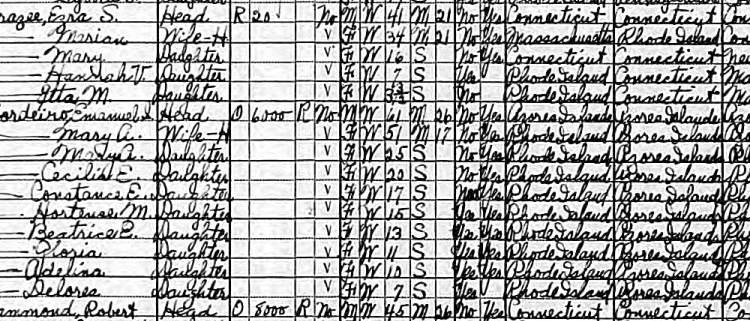

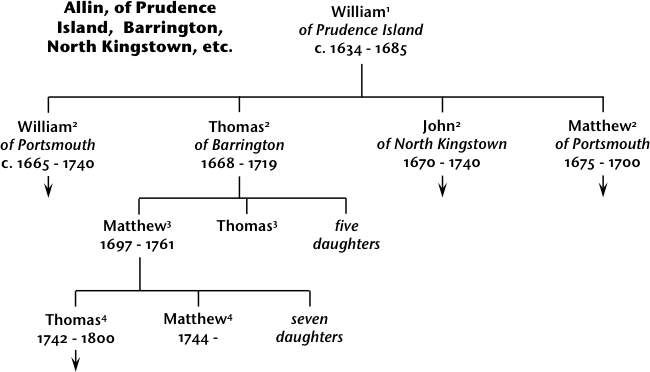

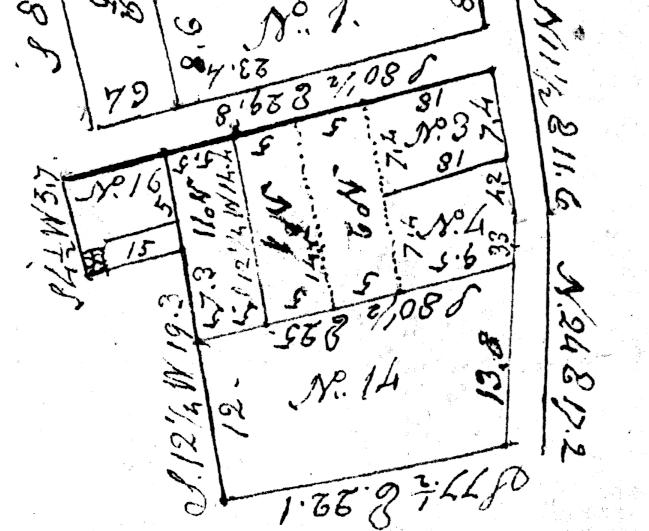

Over the last month I’ve continued to burrow into the history of the General Allin house. The 1930 census had showed two families living in it, and deeds going back to the 1871 plat with a division line transecting the house showed that the west wing was separately owned. Now the ownership of the house has been fleshed back from the 20th century, and forward from the division of General Allin’s estate in 1802. Meeting in the middle has delivered a surprise and further complication — on the death of widow Amy Bicknell Allin in 1827, the portion of the house and farm property she held in dower (which had for some reason not been assigned residuary legatees under the General’s own probate), were subject to dispute by the heirs. “Allin et al. v. Carpenter et al.” reached the Court of Common Pleas of Bristol County, Rhode Island, which appointed a commission to divide the dower property in the winter following Amy’s death. Barrington land evidences do not include a copy of the outcome, but the commissioners’ report and division, with beautiful plat, are engrossed in the act book of the court, now at the Rhode Island Judicial Records Center.

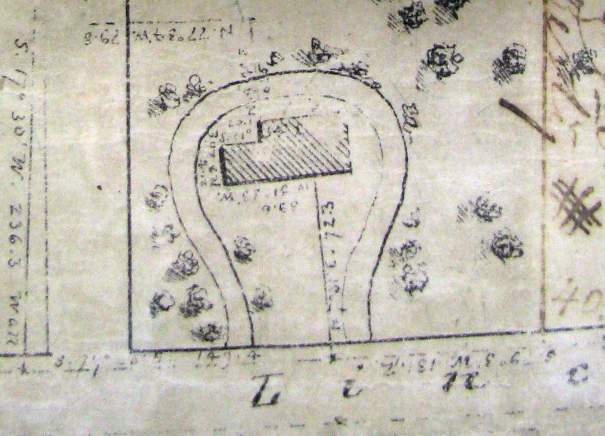

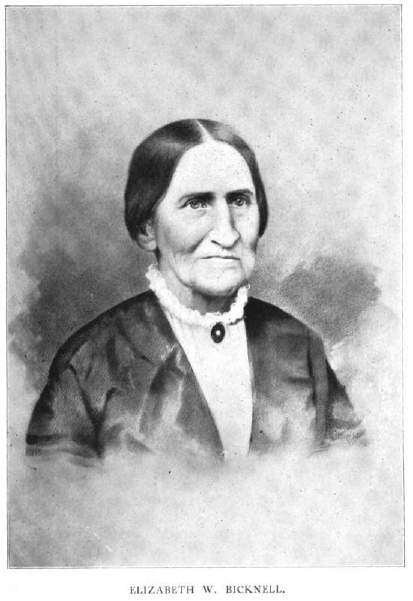

The upshot is that the house (which appears as the little X’d-in chunk at the left of this plat detail) was at that point divided into three legal parcels. Two-thirds of the house had been set off to General Allin’s son William Allin back in 1802, who sold it to his brother-in-law Joseph Rawson, who still held it in 1828. Widow Amy Allin’s dower, including the other one-third of the house and some eighty acres of farmland, was subdivided into over a dozen carefully apportioned shares, including two shares which included rooms in the house and strips of adjacent land. Amy’s daughter, widow Nancy (Allin) Drown, received, as part of her one-sixteenth share of the whole dower property, “the South West Great Room on the lower floor of the Mansion House and Bedroom adjoining, and all that part of the Cellar under the Front Entry and Great room, lying South of a line drawn from the South side of the West Cellar window to the South side of the foundation of the Chimney,” with an adjoining strip of land (no. 15 on the plat). Nancy’s sister, Elizabeth Allin, spinster, was given, as a part of her one-sixteenth share, “the South West Great Chamber and Bedroom adjoining, the Garret West of the Garret stairs, and that part of the Cellar under the Great room lying North of a line drawn from the South side of the West Cellar Window to the South side of the foundation of the chimney,” with a bigger adjoining bit of land (no. 16 on the plat). Elizabeth Allin would go on to recover her sister Nancy’s part of the house and adjacent strip of property, though I haven’t found the instrument for this. Elizabeth then, in the 1850s, built a new west wing onto her part of the house. There may have been a handshake by which she passed her rooms in the old part of the house to the then owner of the remaining 2/3 of the old house after she built the west wing, because it seems that the house more naturally is divided into ‘old house’ and ‘new wing’ units (separated by a single doorway on both floors). This seems to be the division which would persist until 1950, rather than a more elaborate division which reflected 2/3 and 1/3 shares within the old house itself. But the floor plan west of the chimney mass in the old house has been somewhat altered on both floors, so it is hard to tell where the property line would have been understood to go. Only this year, for example, are we finally planning to restore daughter Elizabeth’s ‘southwest great chamber’ to its original proportions. Our own daughter, who is getting that room, will hopefully appreciate the restored symmetry of the great Georgian fireplace surround, with built-in cabinets — the finest original woodwork in the house, of which Amy and Elizabeth must have been proud:

(In this photo, imagine the wall on the left removed, and the room widened to include a matching cabinet left of the fireplace, which is now buried behind a cedar closet. Feel free to imagine the ceiling fan gone too…)