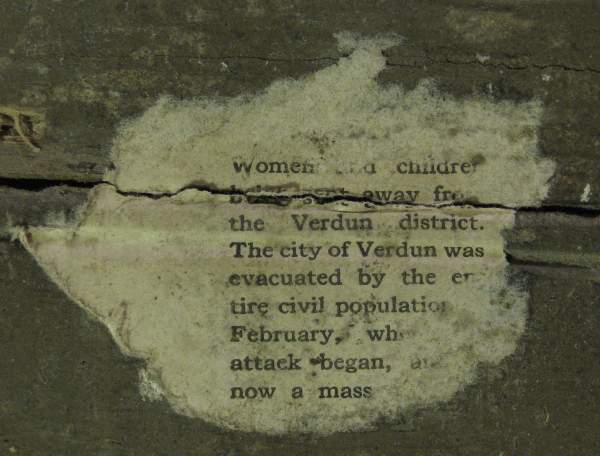

OK, here’s an amazing find, as selective demolition peels back layers of the Allin House. I have already blogged some of the scrap papers — farm accounts, legal memoranda, navigational trigonometry, surveying — pasted down to the vertical plank walls which survived in the ‘West Garret’ in our attic. This week, removal of the modern lath & plaster in the one finished attic room which unfortunately unseated the remaining vertical planks which had been reused as studs, also uncovered several other papers pasted down to vertical planks. The most spectacular find is this (sorry for the size):

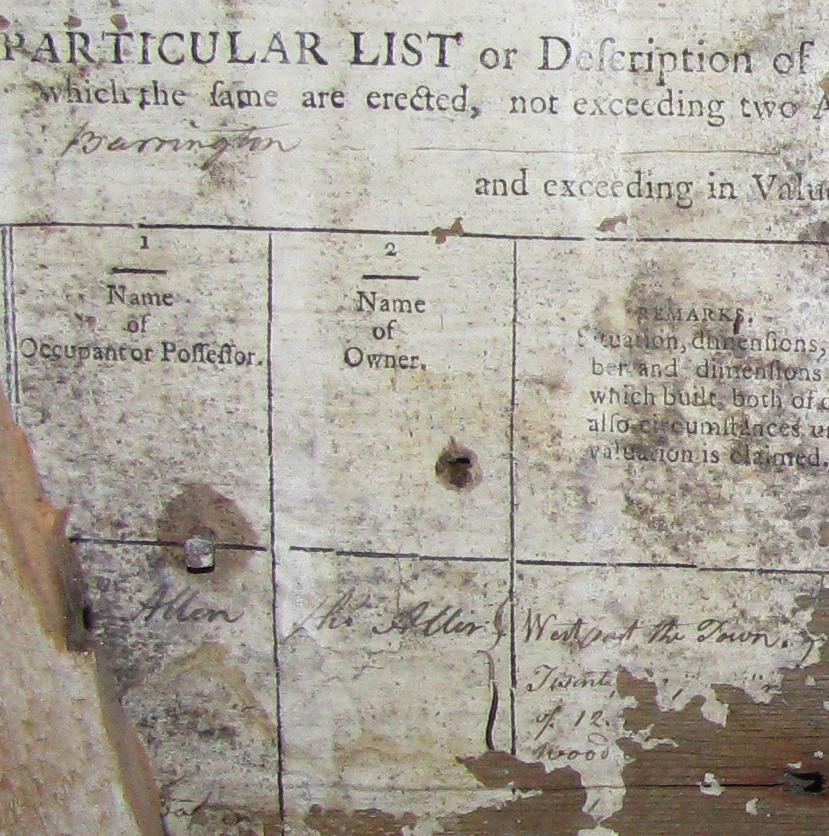

This is bizarrely self-referential: it is a page of the original tax assessment schedules for the town of Barrington (Rhode Island), compiled for the direct federal tax of October 1, 1798. This page lists this house: Owner Thomas Allin, one dwelling, two outhouses, 255 acres.

A finding aid at the Rhode Island Historical Society tell us that these assessments do not survive for most of Rhode Island: only one page of one schedule for Barrington (listing slaves held by four property owners) survives.

The whole page (click the above for a full-size photo) is unfortunately too abraded to show the valuation of the property, or most of the words of its the textual description. And I can’t tell whether this was the top of a sheet which might have listed other properties, or merely a draft for this house alone. And how on earth did it end up as wallpaper in the garret?

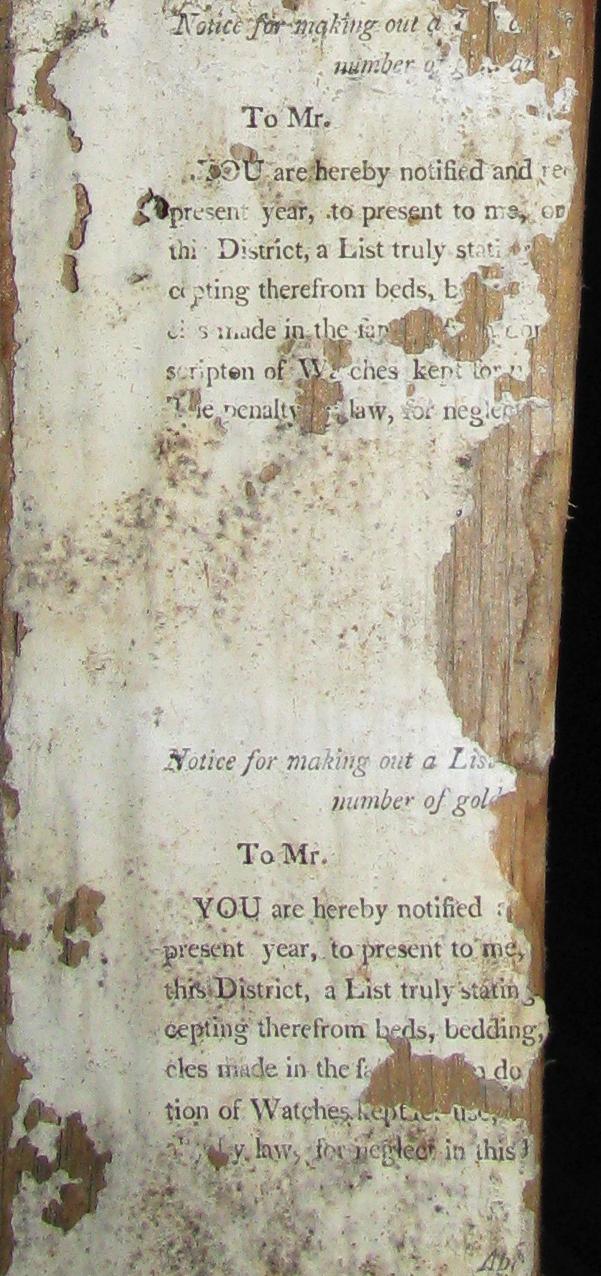

Adjacent to this page are two copies of blank forms used by the assessor to collect data:

Presumably these would only by lying around in the home of the tax assessor himself, a role which Thomas Allin may have played (among his other hats) in 1798.

While other documents had dates going back to the 1750s and even 1740s, these 1798 tax assessment forms give us a terminus for the papering of the garrett. I’m guessing this was done in the time just after Thomas Allin’s death in 1800, when the house was reorganized and someone like Amy Allin’s maid might have lived up here, papering the garrett with scraps from the general’s papers.