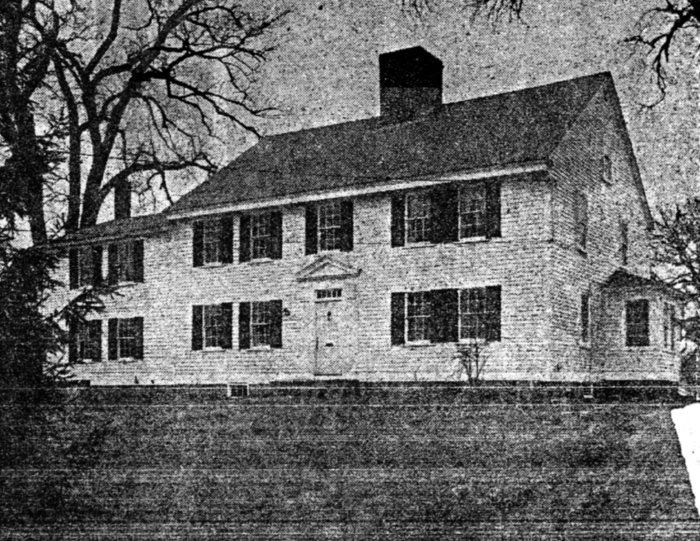

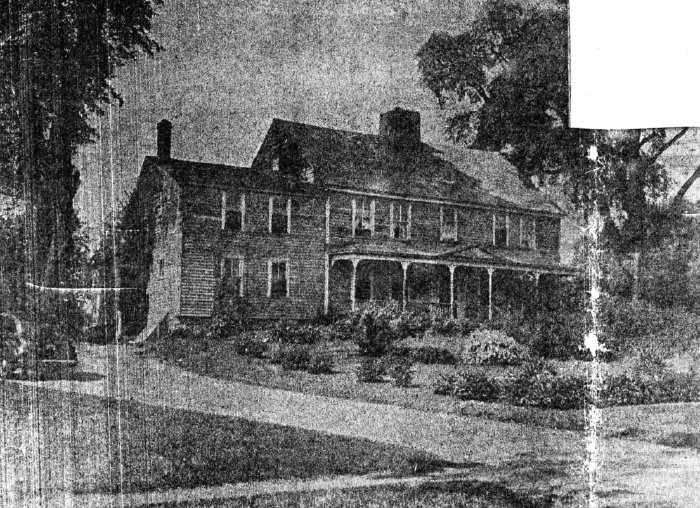

Yesterday the Providence Journal ran a fine, reflective commentary piece by editor Edward Achorn, “A little cemetery and the people who made America,” about his recent visit to the Allin family burying ground, down on Bay Spring Avenue, and the role the Allin brothers, General Thomas and Captain Matthew, and Thomas’s freedman, Scipio, played in the Revolution and the founding of the nation.

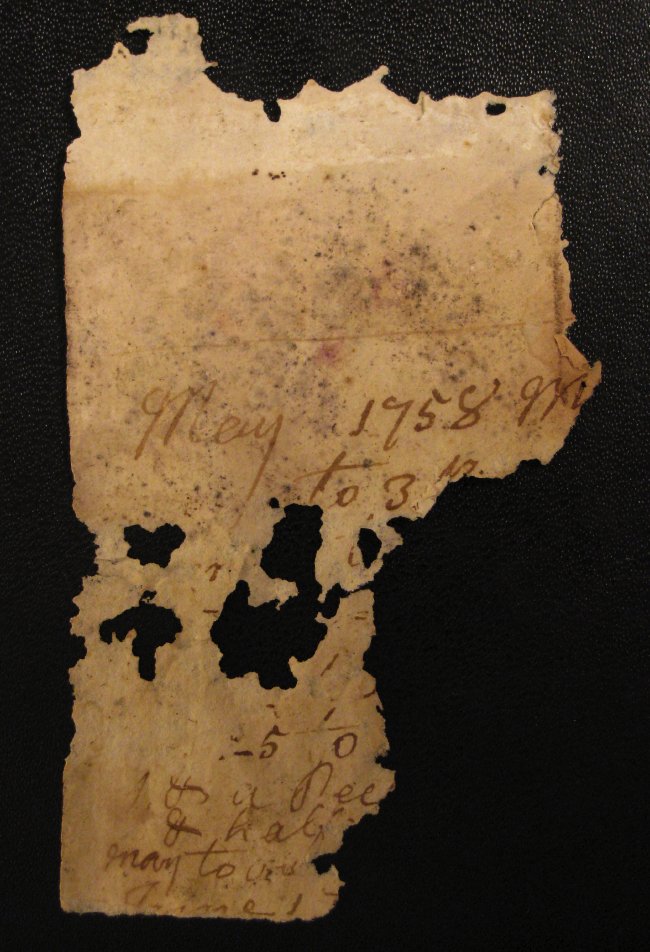

I realize with all our focus on Thomas Allin’s house, I haven’t posted photos of the Allin burying ground here, though I have visited it frequently since the Spring. There are many members of the extended family, descendants and cousins of Thomas and Matthew, buried in this ground, including many who lived in the house. Here are two photos taken this spring on one of my first visits to the graveyard. First, the general himself:

And this long view, with the grave of freed veteran Scipio Freeman in the foreground:

The dramatic setting puts Scipio at the front and center of the graveyard, with all the white folks clustered away at the back, between trees. The graveyard originally had another orientation: Bay Spring Avenue itself wasn’t laid out until October of 1802 (in the division of Thomas Allin’s farmland), and the side street, Adams Ave., didn’t exist till long after. The resting place of the people of color, meant to be something apart, is now in the place of honor, as the graves are approached past Scipio’s lone sentinel stone. (As Edward Achorn suggested, Scipio was likely buried among other slaves or free people of color, but only his stone marker survives above ground.) Many area graveyards embed subtle stories of the changing place of people of color in the community. Some time ago I posted on this in a graveyard near our current home in Rumford, with the beautiful graves of two slaves, Sherrey and Anna.

When I am able, hopefully in the fall, I will take more photos of the graves and, perhaps, work them into an annotated version of the Allin family tree.