Earlier I wrote about a 260-year-old will, signed and sealed by one of my ancestral uncles, which made its way into my possession, as an ‘instant heirloom’, through an extremely narrow form of directed marketing: a dealer in old manuscripts had researched the author of this will online, which led him to my book on the testator’s family, following which he offered to sell it (and I accepted). But there’s another way to get an instant heirloom: the sudden provision of a provenance for something which has always been around in your possession, but which hadn’t been noticed for what it was.

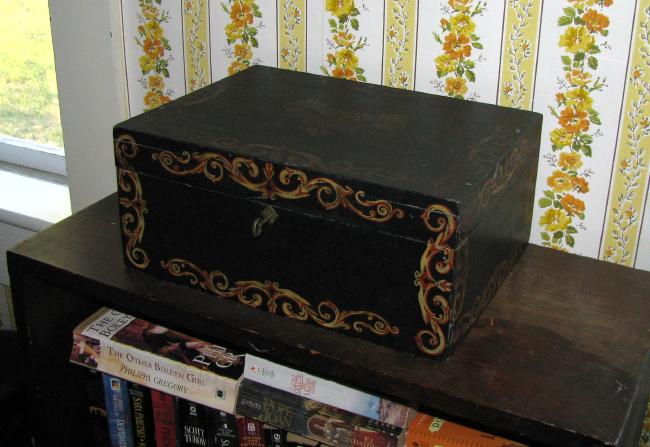

In the front parlor of my wife’s family’s village house in East Washington, New Hampshire, an old painted wooden box has sat on a bookcase for as long as I’ve known it — near 25 years:

Today my son was fiddling with it, observing that the key didn’t seem to work, and he couldn’t get it open. I took it in hand, worked gently with the key, and opened the box, not remembering if I’d ever done so before. (The mellow brass key is obviously original to the box, and the lock is really nothing more than a spring latch, openable when the key is turned slightly).

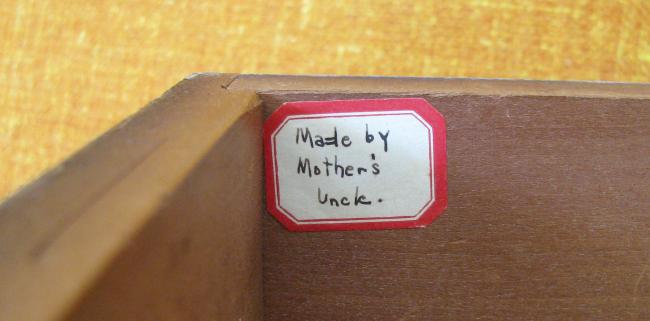

Inside the box, nothing but a spool of white thread. And a small octagonal gummed paper label with a caption — of a type I recognized — saying, simply, “made by mother’s uncle.”

So, whom, and when? The painted decoration is much darkened on the top as opposed to the sides, but the center of the lid bears initials, dark but legible, ‘R.D.’.

And the labels I’d seen before, on other heirlooms. The label writer was aunt Hazel Harmon, sister of my wife’s father’s mother’s father. Her mother was born Rosa Dudley. And I know Rosa’s uncles (her mother’s brothers) were woodworkers, Horace and Lyman Hotchkiss (b. 1809 & 1812). One or the other of them made the birds-eye maple table in our living room (also identified, inside, with one of Hazel’s stickers). Perhaps the same man who made the table made this box for his niece. Rosa was born in 1857, and this might have been made for her as a girl or teen, say around 1870. Here she is:

I have already drawn up a pedigree showing the origin of several Harmon family heirlooms, including the Hotchkiss table, so it is not difficult to add this.

So: the box, sitting here unnoticed for years, is suddenly transformed into an heirloom with known provenance. Moving past the obvious ‘label your stuff!’ lesson, I wonder: how does this new (or recovered) knowledge really transform this box? It’s all in the eye, or memory, or associations, of the beholder. If an object which sat for years with no such associations, suddenly recovers them, is it really an heirloom in the same as any long-cherished token? Or is continuity of sentiment important?

Post a Comment