Tuesday, December 29, 2009

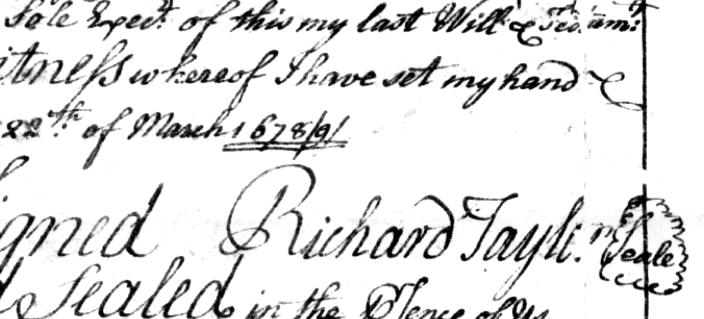

Well, to leave aside DNA for a moment and get back to real, paper genealogy, an e-mail last night told me that the first half of my article on the beginnings of our Taylor family is now out in the new issue of The American Genealogist — even though my copy hasn’t yet shown up in the mail. The article gathers the known data on the first three generations of the family in Virginia, and lays out a new theory for the origins and parentage of the founder of the family, Richard1 Taylor of Old Rappahannock County (subsequently Richmond County). Here’s Richard’s will:

Interested readers should buy the issues and support The American Genealogist. The new origins theory is not currently found in my e-book on the family.

Saturday, December 26, 2009

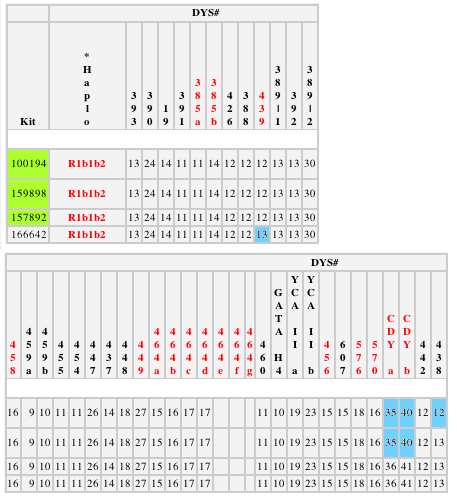

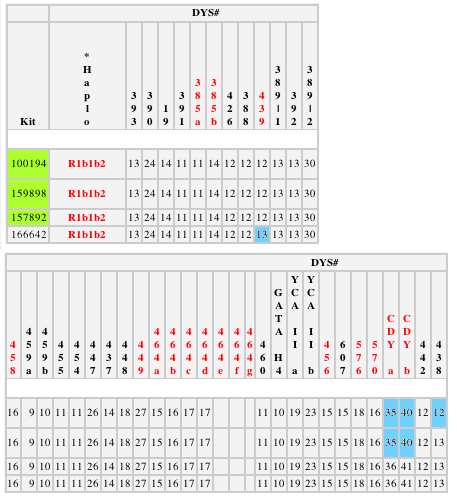

The last time I blogged this we had just received preliminary data from a fourth member of our family to be tested, a cousin whose data pushes the ‘common ancestor’ back to Simon2 Taylor, who died in 1729. Now more of this cousin’s data are available, yielding the following data table:

This raises some interesting questions about interpreting DNA data. Judging only from the discrepancies in loci 34 and 35, the first and second subjects look more closely related, and the third and fourth also. Following the pedigree chart in my last Taylor DNA post shows that this is true for the first pair, but not for the latter pair: the third subject is more closely related to the first two, than to the fourth subject. The fact that nos. 1 and 2 share a common ancestor whose father was the ancestor of 3, and whose grandfather was the ancestor of 4, suggests that the values held by 3 and 4 in those loci are the original values, and that the common ancestor of nos. 1 and 2, Harrison Taylor, was the man who had a spontaneous mutation in both loci, 34 and 35. This is based on the assumptions that (1) the people in this DNA sample are related in the way they are shown to be by the traditional genealogcial evidence; and (2) when two people with a known common ancestor share a particular DNA STR value in a given genetic locus, then their common ancestor also had that value, since the probability of two identical mutations occurring in near cousins is statistically insignificant. Unless one of these assumptions is wrong, then we conclude that the third and fourth subjects determine the ‘original’ values for their common ancestor, Simon2 Taylor; and furthermore only locus 9, out of the first 37, remains ambiguous for the common ancestor, Simon2 Taylor (1667/70 – 1729). We are in the process of collecting more detailed data, to build an unambiguous 67-marker profile for Simon2 Taylor. This chart might help:

To test this theory (that Harrison4 Taylor is the originator of mutations in both loci 34 and 35), hopefully we can secure samples from a descendant of another of Harrison’s sons, as well as from the descendant of Septimus3, brother of George3 and John3, who has already agreed to a test. So there is more to come!

Monday, December 21, 2009

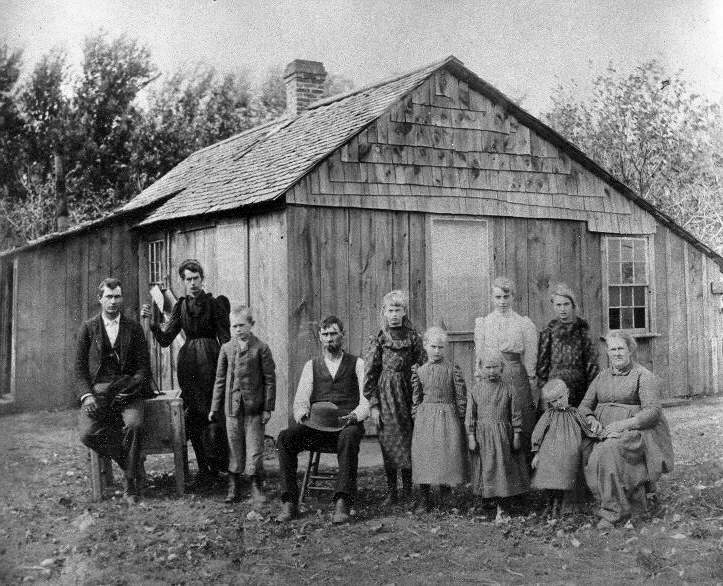

Just the other day I uploaded a new revised version of my book on the Taylors — see here for the download page — and thought I’d signal it with one of the new included photos.

This is James Wesley Taylor (1853-1896) of Tama County, Iowa, and Meade County, South Dakota, with his wife Mary Evangeline Wise Taylor and their extended family. It comes from Darryl Brent Adair, of Texas, whose meticulous research into this particular branch of our Taylor family has formed the basis of some of the recent edits. Here is what Darryl wrote about this photograph:

. . . My favorite old-timey photo probably taken in Tama County Iowa before this Taylor family moved to the Black Hills of South Dakota (Continued)

Friday, December 18, 2009

This morning I gave an exam to three students in the ‘Pavilion Room’, a formal dining room or parlor added to the Victorian house at Brown University which now houses the History Department. And I brought my camera to photograph the wood coat of arms, on the amazing scallop-shiplapped chimney hood:

More or less argent a lion rampant gules, on a chief sable three crescents or. Papworth doesn’t give us anything close to this (1:105 is where the lions with stuff on a chief are found). Burke’s general armory (1032) may get us into the ballpark, with the only family using ‘fortis non ferox’ as that of Trotter, and specifically a Trotter family that combines a lion rampant (azure) and a chief (ermine).

Unfortunately no such imaginative late-Victorian Providence Trotter is found in Crozier, Bolton or Matthews. I suppose I’ll have to look up the house itself, but it would be more fun to smoke this out another way. Not a plaque or brochure at all in the house itself, mind you, except those relating to Mr. Peter Green, the late 20th-century benefactor after whom the house is now named.

UPDATE: the family is Kimball — see comment.

Thursday, December 17, 2009

Good news! Following work begun in the summer and already blogged here, and here, we now have another matching DNA sample from another branch of our Taylor family, which pushes the ‘most recent common ancestor’ of all test subjects back another generation, to Simon2 Taylor.

The chart shows the new addition, test subject no. 166642, whose ancestor, George3 Taylor, was brother of the common ancestor of all the previous subjects, John3 Taylor. Not all the data are in, but he so far matches the rest of them 24 for 25. Now to find a descendant of their brother, Septimus3 Taylor, who would agree to testing. There are extant male lines of descent from Charles4 Taylor, son of Septimus3, in Mississippi and Texas; hopefully someone in this part of the family will be interested and able to participate.

UPDATE: have now made contact with male-line descendants of Septimus3 Taylor, and testing is planned in the near future!

Thursday, December 17, 2009

Ph. Schillinger

To his Beloved Wife

Phillip Schillinger (1831-1888) and Katherine Jenne Schillinger (1832-1918) were my father’s mother’s mother’s parents, German bourgeoisie in Louisville, Kentucky, whence they had immigrated in 1854 and 1855 from the small town of Kippenheim in the kingdom of Baden-Württemberg. Schillinger was a brewer, and this hideous-toothed beer-drinker from an ad for his brew was an early trophy of my genealogical digging. How I came to find many generations of their ancestors in Kippenheim — quite by accident during a job interview — is another fine story.

But to the watch. This month it came to our possession and of course the first thing I did was photograph it; the second was take it to someone to have it looked at, to see if it could be restored.

For as long as I had known it it had lacked a crystal, and the minute hand. I assumed I would be told it was hopeless, or prohibitively expensive, to restore. But I took it to a good, old watch place here in Rhode Island, and was astonished when one of the artisans simply wound it up and it seemed to run fine (of course we have no key to have tried on it ourselves). But the lack of a crystal is a problem: without it, the watch dial, hands, and presumably works are vulnerable, and it is only worth cleaning the works and considering wearing it if a crystal can be found to fit it. The folks will need to search for a perfect-fitting crystal in a hundred years of old stock, then fit a hand to match the size and style. I will be patient and hope this works! I would love to see my wife, or one of my daughters, wear this red-gold watch on its long gold chain with enameled & gilt slide brooch. More pictures after the jump. (Continued)

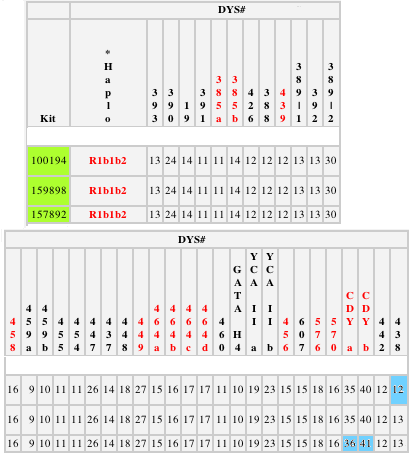

Well, apparently I don’t know how to scrape the inside of my cheeks properly, since the lab took extra long to culture my Y-chromosome DNA. But I finally have a complete 37-marker Y-chromosome DNA test back, so now our Taylor family has three datapoints from which to triangulate a historical haplotype for our common ancestor, John3 Taylor (d. 1741). Here is the data from three test subjects, including me, in the tabular form published by familytreedna.com:

There are three boxes highlighted in blue, in which one value does not match the value for the others. 100194 differs from the others in the last locus, and 157892 differs from the others in two other loci (nos. 34 and 35 out of 37). Each disagreement between values represents a mutation somewhere in the family tree, but where? (Continued)

Just an odd bit culled from the website of the Times — Robertson Davies, writing in 1990, reminded us that Hallowe’en should be a good time to “revive the custom of giving some respectful heed to our forbears:”

[O]ur forbears are deserving of tribute for one indisputable reason, if for no other: without them we should not be here. Let us recognize that we are not the ultimate triumph but rather we are beads on a string. Let us behave with decency to the beads that were strung before us, and hope modestly that the beads that come after us will not hold us of no account merely because we are dead.”

He didn’t mention All Souls’ Day at all — he was haranguing those whose holidays are marked at the drugstore, not a church; read the whole piece here.

Monday, September 28, 2009

I’d been meaning to get into this for a while but had put it off. I’ve tracked my extended male family — on paper — for 17 years now (see my book). But what if DNA testing showed I didn’t belong? Not that I fear skeletons in my closet (or my ancestors’ closets), but I didn’t want the quandary of questioning the value or applicability of something I’d spent so much time on, if it were to turn out I wasn’t actually biologically related. At any rate, others got feet wet first and, following a fifth cousin’s lead (and the persistent prompting of another possible distant kinsman), I signed up for a 37-marker Y-DNA test at familytreedna.com. Results are now in (for me, only partial results at this time), but they prove we are related, and show another Taylor, a seventh cousin, is also (we all share a precise 25-marker profile, and the other two subjects differ in 3 loci in the panel 26 to 37). Depending on what my last 12 markers (not yet back from the lab) show about these three divergent loci, we will hopefully be able to deduce a 37-marker Y-DNA haplotype of our common ancestor, John3 Taylor of Richmond County, Virginia (1703-41). Once other Taylors, descended from John’s brothers, are tested too, we can hopefully then confirm the Y-DNA haplotype for Simon2 Taylor, who must be considered the genetic founder of the family since there is no way to triangulate a non-mutated haplotype for his father, the apparent immigrant, Richard1 Taylor (Richard1 had another son, also named Richard, but the son Richard cannot be shown to have had a family). Here is a chart showing the the early generations of this family which left extant male issue, with lines down to the three subjects already tested (I’m the one in the middle):

John3 Taylor had twelve male-line grandsons who left further male issue. But for John’s brothers Septimus3 and George3, we do not know whether some of their sons left male descendants of their own (hence the question marks): other Taylors show up who may be their sons, but the documentation is too sparse to show it. This is precisely the area in which Y-DNA testing can aid this genealogy, once the haplotype is fully established.

Back to ‘paper genealogy’, the first of a two-part article of mine on the possible English origins of this Taylor family is slated to appear in the next number of The American Genealogist.

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

A propos the last post. A fine obelisk with leaves and flowers in deep relief. Photo from late fall of 2000.