Browsing somewhere online the other day, my eye jumped to a newly-published regimental history of the 10th Kentucky Infantry in the Civil War. This was the regiment of my great-great-grandfather Samuel Matlack (1815-1881), regimental quartermaster, then lieutenant and aide-de-camp on the staff of Brig. General Speed S. Fry, at Camp Nelson, Kentucky.

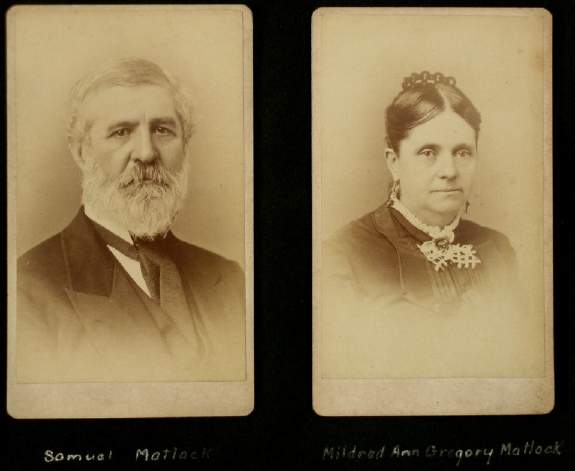

Samuel and Mildred Ann (Gregory) Matlack, in my grandfather’s photo album.

Beyond his own Civil War record Matlack has long held my interest for the unknowns of his family history. According to his obituary in a Louisville newspaper, Samuel Matlack was born in Fairfield County, Ohio, in 1815, son of another Samuel Matlack and his wife Elizabeth Lynch. But there the issue gets complicated, as there were two adult Samuel Matlacks in Fairfield County, Ohio in the early nineteenth century. Over the years I’ve drafted a study of these Matlacks, trying to reconcile various (unreconcilable) statements in sources which appear to mix them up, and trying to discover their relation to the Quaker Matlack family of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, to which they apparently belonged. In the process I’ve discovered various weird anomalies about (as is often the case) the other Samuel Matlack’s family. I just realized I never got around to putting this unfinished work online. In the hopes that (as has happened before) search engines might attract others with insights, I’m doing so here:

Click to read (pdf) “The Two (or Three) Samuel Matlacks of Fairfield County, Ohio.”