Wednesday, March 18, 2009

One of the hidden treasures that has rewarded my browsing in The Ancestor (of which I recently bought a set of all twelve volumes in their original publisher’s bindings), is a handsome set of cuts made after fourteenth-century encaustic floor tiles from Tewkesbury Abbey. See Hal Hall, “Notes on the Tiles at Tewkesbury Abbey,” The Ancestor 9 (1904), 46-64. The digital copy of the journal (linked here) contains fine scans of these, of which the following sample set of eight (there are several others) are reduced in size and flattened nearly to black-and-white. The captions here are as given in the article. Excellent source of dingbats for a heraldry blog!

Arms of Somerville of Gloucestershire

Arms of Somerville of Gloucestershire (Continued)

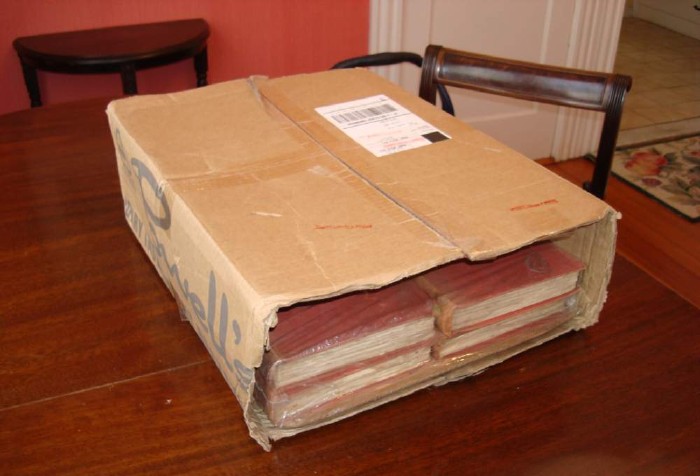

It’s the plot of an old romance film mapped onto a common genealogical trajectory: boy meets ancestor, boy loses ancestor. Marshall Kirk used to talk about ‘former ancestors’—people you once believed you were descended from, and of whom you still might be fond. Sometimes they even find a way back into the family tree via another path. This just happened to me, not with actual ancestors, but with The Ancestor. While I was writing, recently, on The Ancestor and its editor Oswald Barron, and admiring the journal in its online form at archive.org, I was put in mind to shop for an actual set. A big west-coast used bookseller had the twelve-volume complete run for an astonishing $56, shipped free via USPS ‘media mail’. I ordered it without blinking and looked forward to its arrival. Imagine my dismay when a tattered, gaping open box showed up on my doorstep with just six volumes, held in by clear tape, the box itself missing one end and festooned with stamps stating “Received in Damaged Condition.”

(Continued)

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

[Part of a series of posts and pages dedicated to Sancha de Ayala]

More photos of Sancha de Ayala’s maternal ancestral home, the Ayala stronghold at Quejana (Álava), near Bilbao. It is fascinating, and fortuitous, that the houses of both Sancha de Ayala’s paternal and maternal families have been preserved since the fourteenth century due to their conversion into monastic establishments. Quejana is now a Dominican convent, and the old family chapel is now dwarfed by the late-Renaissance convent church (where Fernán Pérez de Ayala, Sancha’s first cousin, is buried). But the older palace chapel, built by Sancha’s uncle, the Chancellor Pero López de Ayala, as a resting place for his parents—Sancha’s grandparents—still houses their tombs and the relics of the Virgen del Cabello (our lady of the hair) with an elaborate painted retable commissioned by the Chancellor—on which later.

The alabaster effigies of Sancha’s maternal grandparents, Fernán Pérez de Ayala and his wife Elvira de Ceballos, now rest in niches in the chapel, (Continued)

Monday, February 23, 2009

In Brigitte Miriam Bedos-Rezak’s review of Ted Evergates’ Aristocracy in the County of Champagne, 1100-1300 (U. Penn. Press, 2007), just out in American Historical Review 114 (2009):192-3, she is not the first to point out how Evergates contradicts Duby’s orthodoxy by showing that the most important aristocratic family unit is not the lignage, but rather the nuclear or conjugal family. When I first saw this in another review (probably TMR) I read Evergates carefully. He does not busy himself destroying paradigms, but he does convincingly show the primacy of the conjugal family in many aspects of aristocratic economic and social life in Champagne. I am sure that he would not deny that, elsewhere and even in Champagne, certain types of evidence do show the rise, in the 11th and 12th centuries, of the land-based agnatic ‘lignage’ as a model for identification of one’s extended family; but Evergates’ work reminds us that this paradigm (or other paradigms of spiritual and commemorative kinship), no matter how compelling, should not lead us to neglect the day-to-day importance of the conjugal family; and especially that women were not (as Duby implied) necessarily systematically victimized and disenfranchised in aristocratic society—so long as they married.

In her review Bedos-Rezak makes one interesting suggestion—that more attention could be paid to seal epigraphy and and iconography—including heraldry—as a way to trace the evolution or relative strength of agnatic lineages in self- and family-identification. Here’s an interesting way to take an old and marginalized antiquarian field and make it relevant to the current social history! Of course, given that the trend of heraldic identification on seals only appears late in the ‘mutation féodale’ timetable, there is the potential pitfall of a ‘mutation documentaire’ suggesting false societal trends, but reviewing the evidence for such a comparitive study would be a fun way to look afresh at a corpus of seals…

Sunday, February 22, 2009

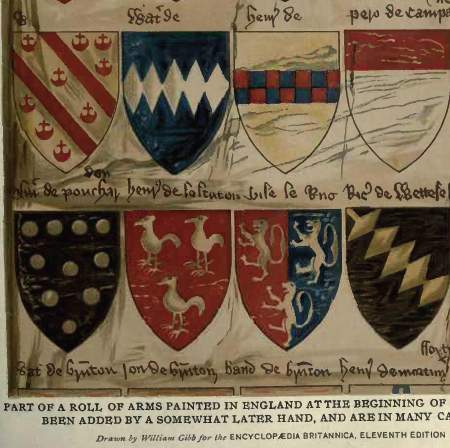

Not everyone agrees with all of Oswald Barron‘s opinions, but he is one of the revered champions of the golden age of critical genealogy (and other auxiliary historical disciplines) in late Victorian and Edwardian England. His own short-lived journal, The Ancestor, is a splendid readable collection of critical genealogy—Horace Round was a regular contributor. All twelve volumes are accessible on archive.org, and even (surprisingly to me) available at reasonable prices, in the flesh, from some antiquarian booksellers. I’ve extracted Oswald Barron’s learned diatribe “Heraldry Revived” from the first issue of The Ancestor, and also for good measure his magnificent illustrated article “Heraldry” from vol. 13 of the 11th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (which everyone should also have in its entirety on their laptops).

(Continued)

Friday, February 13, 2009

In the Rhode Island Historical Society library is a strange heraldic treasure — a grant of arms, from 1631, to a George Thorold of Boston, Lincolnshire. It is a copy, probably from the beginning of the 18th century, darkened and greasy with long handling and haphazard storage. The copy is inexpert—the lettering is unstudied, and the painting of the arms is atrocious. This copy of the grant apparently belonged to another George Thorold, who came to the other Boston, in New England, around 1700 and died at New York in 1721, leaving three ‘Orphaned’ unmarried daughters, one of whom in 1773 summoned her minister (who happened to be Ezra Stiles, later president of Yale College) to write down, on the back of the same document—probably condensing and paraphrasing from her rambling narration—a curious genealogical memoir: “Mrs. Anne Sabin, widow, aet. about 70, now living in Newport, desires me in her Presence to write this account…”

The account is of the descent of her father George Thorold of New England from the earlier George Thorold of the grant, with of course the added drama of a lost legacy of £1500 due to New England George’s three ‘Orphan girls’, and a stoutly claimed kinship to another George — Sir George Thorold, Bart., Lord Mayor of London at the time of his New England namesake’s death, and supposedly second cousin of the girls. Despite machinations and some Newport friend’s trip to London, all that came of the long-sought legacy and claimed kinship was one guinea, hastily proffered by a London Thorold, for gowns for the three needy Thorold girls in the colony. After fifty years it still rankled. So, as Stiles concluded, “at Mrs. Sabin’s desire and in her Presence I have here made her memoir for the Gratification of her Posterity.” One can almost feel Stiles’ sense of this tale as improbable, or at best futilely burdensome. Why pass on such a tale—would it ‘gratify’ her posterity? (Continued)

I just rediscovered the digitized microforms of the Revolutionary War pension files (pensions granted from 1832 onward) available from ‘HeritageQuest’ via many subscription libraries (including the Boston Public Library, for Massachusetts Residents, and many other public libraries throughout the US). By my count my children have 39 ancestors listed in the DAR Patriot Index, of whom 28 apparently saw military service (almost all in local militias, not Continental Army units). [I have 16, of whom 11 saw military service; my wife has 23, of whom 17 saw military service. She has all the militia officers too — a couple of captains and three lieutenants. See our revolutionary ancestors marked in these four charts, one for each of my parents, and one for each of her parents: MHT, EDT, JRS, PLF.]

Of these 28 military men, six are represented by applications under the 1832 federal pension program, either for themselves or by their widows. Of these six pension applications, four were rejected! The six are (with file numbers):

Andrew Griffin (1758-1829) of Gloucester, Massachusetts — R4316

Willey Hill (1759-1849) of Lee, New Hampshire — R5015

Caleb Lane (1759-1850), of Gloucester — S29961

Jonathan Robinson (1760-1843) of Gloucester — S30072

Richard Taylor (1760-1843) of Frederick Co., Virginia and Ohio Co., Kentucky — R10425

John Wingfield, Jr. (1761-1802) of Hanover Co., Virginia and Wilkes Co., Georgia — R11715

(Continued)

(Continued)

So here I am in Savannah, on a rare occasion when I’ve accompanied my wife to an academic conference but we have not brought any children. Aside from blessed sleep, I’ve been able to be a genealogical tourist when on my own. As it turns out my wife has distant roots in Savannah, her ancestor with the amazing name of John Francis William Courvoisie Armstrong having been born here in 1808 (named after a fellow Savannah resident with whom there must have been some close connection). JFWC Armstrong’s father James Armstrong was an early Baptist who spent some years in Savannah before settling in Wilkes County, Georgia, where several generations of his descendants lived. Julie’s great-grandmother was Selene Armstrong, hence ‘Armstrong’ is one of our children’s ‘seize quartiers’.

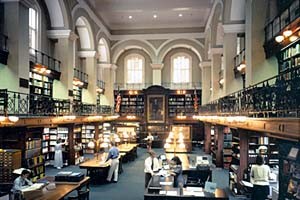

What I knew of James Armstrong, who lived at Savannah from about 1800 to 1820, had come from a typescript by distant cousin Emelyn (Arstrong) Fenenga. But yesterday an afternoon at the library of the Georgia Historical Society —

— got me some interesting additional information on James Armstrong and his two wives, Mary (or Jane), who died at Savannah in 1806, and Elizabeth, whom he married in 1807, and who was mother of JFWC Armstrong. (Continued)

Saturday, January 24, 2009

John Ross Delafield (1874-1964), a scion of New York’s pre-Gilded Age oligarchy, appears to have been the man who invented the 20th-century practice of honorary grants of arms by the College of Arms for the use of Americans of English (or British) descent.

The practice may well have emerged as a result of the College’s work with Delafield—his interactions with them date from 1916 to, at least, 1932. (Continued)

Monday, December 15, 2008

[Part of a series of posts and pages dedicated to Sancha de Ayala]

The first of a series of photographs of the rural Ayala castle at Quejana, home of Sancha de Ayala’s mother Ines, daughter of Fernán Pérez de Ayala and Elvira de Ceballos (who are buried in the chapel, along with Sancha’s famous uncle Pero López de Ayala). From the distance, looking down into the valley in which it nestles, it seems humble, sort of a fortified compound rather than a castle.

(Continued)