Last night, on the cusp between Father’s Day and Juneteenth, I took a closer look at my male-line ancestors. I knew they had enslaved people in Kentucky, and before that in Virginia. But wills and inventories had told only part of the story. For example, Richard Taylor, who fought in the Revolution, died intestate in 1843, and no inventory survives for him. Richard’s father, Harrison Taylor, who died in 1811, bequeathed in his will a Mulatto woman, Charlotte, “during her servitude,” and Charlotte’s son James, both under some pre-existing term-limits to their enslavement.

Richard’s son Blackstone Taylor (1806-1870), my great-great-great grandfather, died after Emancipation, so his will and inventory do not include enslaved people. But I’m not sure why I never looked for him before now in the Slave Schedules of the 1850 and 1860 Federal Censuses.

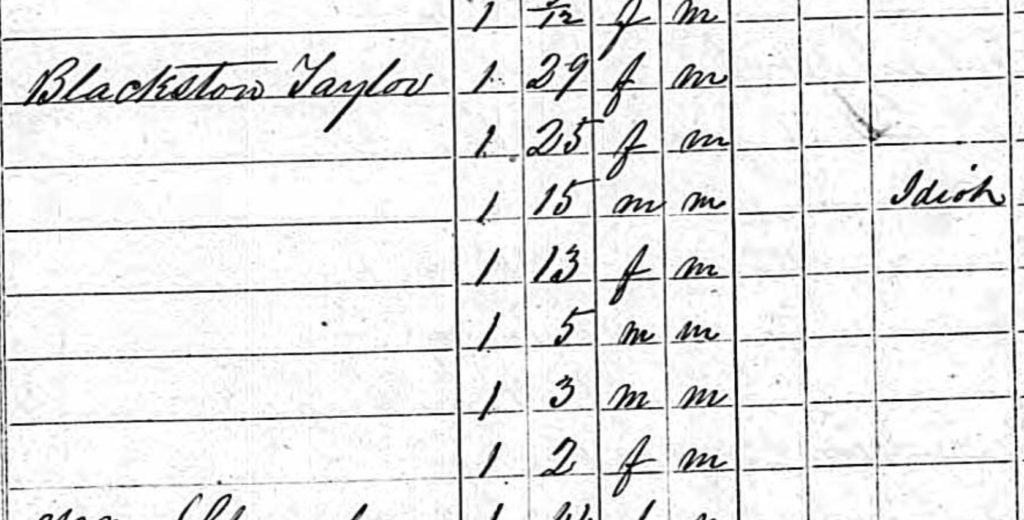

In 1860 he enslaved seven people, ages 29 to 2 years, the 15-year-old boy an “idiot” (1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Deckers Dist., Ohio Co., Ky.). So many people with names and stories to seek.

Post a Comment