In the annals of genealogical fantasists the Conde de Clonard is an interesting case. The condes de Clonard descend from an Irish mercantile family in eighteenth-century Spain, the Suttons of county Wexford, of whom Don Miguel Sutton (hispanized ‘de Soto’ or ‘de Sotto’) was ennobled in 1770 as the ‘conde de Clonard’, taking his title from an ancestral holding of his family in Wexford. Interestingly, in the same generation, another Wexford Sutton, apparently a third or fourth cousin, settled in France, was also prominent in mercantile circles (no doubt participating in the same Atlantic trading network) and was ennobled in France as the “Comte de Clonard.” These two related Sutton branches in France and Spain shared a tradition that the Wexford Suttons were descended from Thomas, a younger son of John Sutton alias Dudley, 1st Baron Dudley, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who died in 1487. However, John, Baron Dudley, had no son Thomas; and the available published documentation on the Wexford Suttons offer no evidence to support a descent from the baronial Sutton Dudleys.

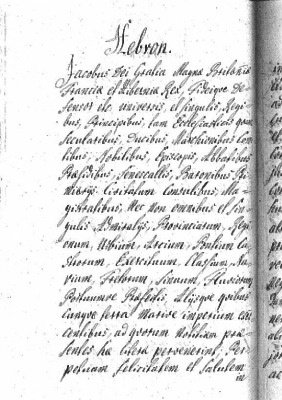

The current conde de Clonard has stated that his family has an illuminated pedigree, 183 centimeters high, prepared and signed by James MacCulloch, Ulster King of Arms, in 1764, giving a genealogy of the Wexford Suttons and stating their descent from John, Baron Dudley (a brief passage from this is quoted here). This would be an interesting document to examine in its entirety, since British documents created to satisfy other nations’ social or legal requirements of noble ancestry have not been carefully studied. They likely were never common; and they were surely subject to a great deal of abuse—either outright forgery, or at least or knowing exaggeration or falsification of information in them even by legitimate authorities. For an example of such a document, allegedly created by King James VI & I in 1616 for use in the duchy of Stettin-Pomerania, see another blog post here.

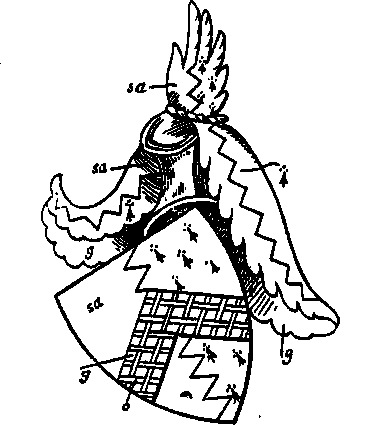

This image, from Clonard’s website, is of a typical 18th-century-style rendering of the Sutton-Dudley arms on parchment. Clonard does not identify it, but it could well be an illumination from the Ulster King of Arms document of 1764.

The current conde de Clonard is José Antonio Guijarro Torija y de Sotto. (Continued)

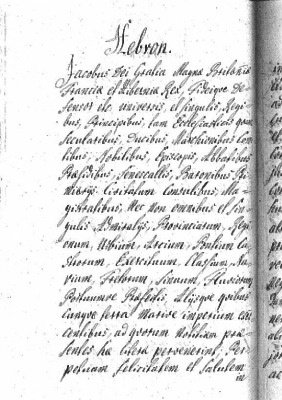

At the request of a correspondent on rec.heraldry I am posting something interesting here. It purports to be a copy of charter of King James VI & I, dated 16 July 1616, which attests the noble ancestry and good character of an expatriate Scotsman, Captain Daniel Hepburn, “legitimate son of the late Alexander Hepburn,” resident at that time in the duchy of Stettin – Pomerania (the document is addressed partly to Phillip II, Duke of Stettin & Pomerania from 1606 to 1618). Hepburn having been the subject of calumnies against his ancestry, King James wishes all to know that quondam Alexandrum Hepburnum ex legitimo matrimonio et generosis parentibus ortum fuisse, et ex nobilibus familiis tam a paterno quam materno genere descendisse. The document goes on to specify that Alexander Hepburn was son of one John Hepburn, virum vere nobilem et bonarum omnium artium studiosum, and that John Hepburn was ‘nepos’ of the late Patrick Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, Lord of Hailes, and Admiral of Scotland. [Right-click on this cap of page 1 to download whole document as a pdf.]

(Continued)

Not particularly strong. This is a classic case of a circumstantial argument for the identity of an early colonist, which (unsurprisingly) connects him to a mother (Margaret Campbell of Keithick) with demonstrable noble ancestry. I have just dug up the two articles by Charles G. Kurz (based on research of Thomas Garland Magruder, Jr.) which build the case for his identity and lay out some details on his alleged mother’s ancestry. For those who are interested and who haven’t seen the original articles, I’ll make them available here for download as pdfs:

Charles G. Kurz [& Thomas Garland Magruder, Jr.], “The Ancestral History of Margaret Campbell of Keithick,” Yearbook of the American Clan Gregor Society 62 (1978), 55-65.

Charles G. Kurz [& Thomas Garland Magruder, Jr.], “The McGruder Lineage in Scotland to Magruder Family in America,” Yearbook … 63 (1979), 53-72.

These articles do make some effort to cite primary sources, but there is no systematic presentation of the strengths and admission of the weaknesses of Magruder’s claimed parentage. Kurz treads very lightly on the idea that these Magruders have nothing to do with the MacGregors, while still indulging in the old game of self-congratulatory worship of noble ancestors. Speaking of which, here’s something a little weird: the mixed-genre poem by Susan Tichy (poet, and Associate Professor of English at George Mason University) called “Heath IV,” a modern reflection on Magruder which of course preserves some of the old canards about his life and spurious relation to clan Gregor.

I am researching the Mackworth family of Rutland and Shropshire, who descend from Thomas Mackworth of Derby, who with his brother John (a canon of Lincoln cathedral) was granted arms privately by John Touchet, lord Audley, in 1404. I was curious about the phenomenon of early private grants of arms until I found the excellent set of examples put together by Sebastian Nelson (now an archivist working for the State of California at Sacramento) on two pages, one for private grants of the fourteenth century, and another for early heralds’ grants (but with an introduction discussing private grants).

The original of the Mackworth grant of 1404 was in the possession of the Mackworth baronets of Normanton (Rutland) at the time of the Visitation of Rutland of 1681-82. (Continued)

A new genetic study (Pierre A. Zalloua et al., “Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Lebanon Is Structured by Recent Historical Events,” American Journal of Human Genetics [2008] 01.020) shows a small proportion of WES1, a Western-European haplotype within the R1b haplogroup of DNA signatures of the Y-chromosome, present among the modern Christian population of Lebanon. The study, by members of “The Genographic Project,” suggests that this genetic legacy (which is inherited in the agnate line, from father to son) is likely to have been introduced by Western Europeans during the Crusades. The actual sample with this attribute appears to be small (5 individuals out of nearly 1000 Lebanese studied) but the statistical arguments for its importance may be sound. This attribute is not found in any other sample studied by the same consortium, east of Hungary.

If the authors’ theory of its historical introduction into Lebanon is correct, it casts an interesting sidelight on the Nachleben of crusading. What was the likely cultural path for the bearers of this genetic legacy, before and after 1291? Were they unacknowledged bastards of the Franks, living among a local Christian population under Frankish rule, whose descendants were fortuitously undisturbed during the long centuries of Mamluk and Ottoman rule? Or were they Latin-Christian Franks who never left after 1291, perhaps adopting a new sect and living a quiet life in the countryside—gone native? More likely the former.

[Thanks to Eastman’s Online Genealogy Newsletter.]

I haven’t actually seen the cable TV serial “The Tudors” but I can understand heavy marketing for its new season to cash in on the recent theatrical release of the unrelated Boleyn film (which owes much to the work of genealogist Tony Hoskins, a probable Henry VIII descendant via one of Mary Boleyn’s ‘Carey’ children). But at any rate today my eye was caught by a glossy magazine spread —

— promoting “The Tudors,” featuring Jonathan Rhys Meyers and Natalie Dormer (as Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn) wearing things unlikely to have been designed in the 16th century. But the text was even more interesting: a sweepstakes offer tied into the show, offering $50,000 plus an “authentic English title such as lord or lady” to a lucky entrant. Presumably a lordship of the manor?

In the fine print of the promotion rules there is the following:

Prize: One (1) Grand Prize includes … an authentic English title such as “Lord” or “Lady”. English titles shall be awarded subject to then-current English legislation, and are non-inheritable and for show purposes only. …

What on earth is a ‘title such as lord or lady’ which is ‘non-inheritable and for show purposes only’? This cannot describe a lordship of the manor, which may be freely bought and sold. Unless the promoter can arrange to have some sort of private lease or lifetime grant of such a lordship, while retaining ownership? At any rate, American credulity in the matter of aristocratic titles is profound and endless, but this seems to plumb a new depth.

As a followup to my post and queries about cousin Wilbur’s (S/Sgt Wilbur F. Whiting, USAAF) sketch for the Scrubbed Goose, the helpful folks over on the message boards at armyairforces.com haven’t been able to locate an actual aircraft with that name, but it could have been a sketch for a plane which was lost before it was christened and painted. But my mother confirms that Wilbur told her he had indeed painted the nose of several B-24s while he was stationed in the parachute shop at Attlebridge field (Norfolk), serving the 466th Bomb Group (heavy) from 1944 to 1945. One of them was Lady Lightning, of whom I have a snapshot from Wilbur’s collection:

A nearly identical photo (!) here is accompanied by the information that this aircraft was shot down over the Netherlands on 15 Aug 1944. (Continued)

I just noticed (via google) that my grandfather is mentioned in a recent book on the war: Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History (Holt, 1994), p. 443, on the allied advance near Soissons on 18 July 1918:

Pershing’s biographer cites the diary of Marvin H. Taylor, who recorded reaching a German machine-gun post where “he encountered a dead German machine gunner seated at his weapon, his hand still on the trigger. He was slumped over, a bullet hole in his forehead and a bayonet thrust in his throat. The gun had an excellent field of fire, and many Americans had died approaching it. Taylor was a humane man, but he laughed aloud at seeing the corpse; it seemed a fit retribution for what the gunner had done to others.”

I suppose now is as good a time as any to break out this item, something lying around unexplained among my grandfather’s WWI memorabilia (in fact, kept in a box with his own medals):

The ubiquitous Iron Cross Second Class, given to as many as four million men during WWI. The question: was this liberated from someone like the unfortunate gunner in the box near Soissons? My father and I recently admitted to each other that we had suspected the same thing. But maybe (and perhaps more likely) it came from some willing, living hand in the long lines of POWs that junior officers like my grandfather had to tend: perhaps traded for cigarettes, writing paper, decent cheese or something. Hard to say. It is not mentioned in his typed journal (though I haven’t searched all the left-out spidery text of the original letters, where it might still be found). If he never mentioned it, does that fact suggest that it may indeed have been pulled from a corpse, an act of which he was not proud? Or were such mini-trophies passed around through allied ranks without a thought, not considered important enough to mention? While still in training camp in 1917 Taylor had written of his desire to bring back a Prussian helmet. I think, in fact, that he had written this to his girlfriend, whose grandparents were all German immigrants…

It’s hard to comprehend the complexity of the context of this and similar war relics. As heirlooms go, it definitely belongs in the category of ‘what on earth do we make of this?’

I have 70 pp. (out of 250 pp. of the typescript) reasonably well edited. Will work on format & post soon—on the outside site nltaylor.net, not in the blog.

A query forwarded to me by a friend got me interested in the ‘Quaternionenadler‘: a German imperial eagle with the coats of arms of the estates of the empire superimposed on it, a Hapsburg emblem popularized around 1510. Here it is, in a beautiful painted two-page print by Augsburg artist David de Necker:

While it’s a remarkable heraldic display, (Continued)

In the spring of 1917 my grandfather, aged 21, left college to become an infantry officer in the first wave of volunteers for what would be called the American Expeditionary Force in France; he was comissioned lieutenant in August and shipped to France the next month. He saw service in the heavy fighting in northeastern France (Château-Thierry etc.) in the winter and spring of 1918.

He wrote frequent letters to his father and girlfriend, and also filled two small pocket notebooks he kept with him the whole time.

(Continued)