Posting Wilbur’s Air Service Command patch got me to go back over the fragments of his war memorabilia to flesh out his service. He was in England from February 1944 to July 1945, rigging parachutes at an Eighth Air Force Liberator base in Norfolk, but we didn’t know where. It now looks like he was (at least for some of the time, and perhaps all of it) at Attlebridge RAF base in Norfolk, home of the 466th Bomb Group: Wilbur’s APO was that for the Air Service Command supporting the Eighth; and his assigned place at least during September to November (and possibly the whole stretch) was the ‘472nd Sub-Depot’, which was Attlebridge. Wilbur’s snapshots of the depot include two identifiable B-24s from the 466th, and he kept a note of appreciation signed by various comrades including one pilot of the 466th, Capt. Francis Bell, who had hit the silk after a disastrous midair collision on 16 September 1944.

Another mystery in Wilbur’s effects is a sketch and colored illustration which seems reminiscent of aircraft nose art, complete with a vivacious lady and an evocative name. Here she is, the ‘Scrubbed Goose’ [NSFW after jump]: (Continued)

Tuesday, February 5, 2008

Wilbur Floyd Whiting (1919-2006) died just over a year ago, around Christmastime. He was my grandmother’s first cousin. His mother Mamie (Marie Henriette Lembke) was my great-grandmother’s baby sister, and she and her husband Floyd were always close to my great grandparents. Wilbur, their only child, was sort of an auxiliary sibling alongside my grandmother’s five brothers and then someone who my mother saw a lot of as a child. ‘Cousin Wilbur’ was for decades the closest extended family my grandmother, and more recently my mother, had.

Wilbur was a commercial artist, draughtsman and designer, fleamarketeer, repairer of old chairs, and hoarder of stuff. In the Second World War he was in the Eighth Air Force in England. He worked on the ground, repairing and maintaining parachutes and flight leathers, and teaching the craft to others. His memorabilia from the war include astonishing binders of fabrics, grommets and stitch samples; needles the size of pencils; a formal scarf made from parachute silk; drafts of aircraft nose art; an appreciative note from a ‘caterpillar’ (a crewman who bailed out and owed his life to the parachute silk); and his own painted leather patch from the Air Service Command.

Wilbur’s whole patch collection includes his stripes (technical sergeant’s, though his separation papers call him a staff sergeant), a couple of 8th Air Force and Army Air Forces patches, and a Military Welfare Service patch, perhaps from his sweetheart. (Continued)

Tuesday, February 5, 2008

“Why did the first Crusade succeed, and why should it not have?”

I often pose this question, or one substantially like it, in exams on the Crusades, or Church history, or medieval military or political history generally. It is interesting to me how few students take the second phrase as an invitation to a moral judgment. Are historians (or students of history) not allowed to weigh past events and persons, to write about why things should or should not have happened, based on our own moral compasses? Too bad that such liberties should be frowned upon. We are all told that nothing we write can be free of bias. Yet if objectivity is unattainable, why should we not indulge our moral compasses?

One student wrote: ”It should not have succeeded because it was ill-conceived, disorganized, and motivated in large degree by chauvanism, xenophobia, and greed.” In fact, an army largely motivated by those things should succeed quite well, I think: no troublesome scruples or complex perspectives to slow them up.

Katrina Browne’s film Traces of the Trade has now been seen at Sundance, and Thomas Norman DeWolf’s book on the subject has now come out too: Inheriting the Trade: A Northern Family Confronts its Legacy as the Largest Slave Trading Dynasty in U.S. History. This is a Rhode Island story, and a genealogical one. It’s also something I’ve been studying closely for a while. The DeWolfs of Bristol, Rhode Island, got their start in the slaving business when Mark Antony DeWolf was set up in slaving voyages by his brother-in-law, Simeon Potter, slave-ship financier and ex-pirate. Potter (who died without issue) had nine sisters, one of whom married DeWolf and became the DeWolf matriarch (my children descend from another sister). (Continued)

Wednesday, January 30, 2008

For the wonderful cousin in Capetown, Dawn Raimondo, I recently wrote up a brief report (not for publication) on the descendants of Vere Stapleton (on him see previously in this blog). Thought I’d post a separate link to it since I’ve been working on its style & format. Started in Microsoft Word, with a Word-to-html conversion; then stripped out all the bad Word style formatting & integrated it into my css for the main website. Tedious in places, but this is a short report and now that I have a template, I may put together more standalone html page summaries like this.

Anyhow, here it is: De Vere Stapleton: Genealogical Summary.

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

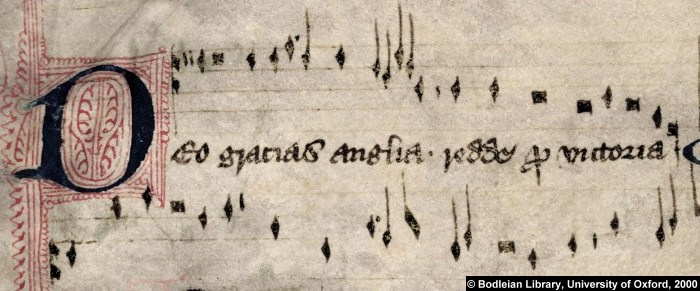

Trolling through hymns while recently masquerading as a substitute organist, I noticed an interesting setting of the melody of the Agincourt carol in the Hymnal 1982 of the Episcopal Church(*), which sent me scurrying back to the edition in William Chappell’s Early English Popular Music (1893). And that sent me to MS Arch. Selden B.26 at the Bodleian Library (one of two original 15th-century manuscripts of it), which I discovered was digitized at Early Manuscripts at Oxford:

(Continued)

Saturday, January 26, 2008

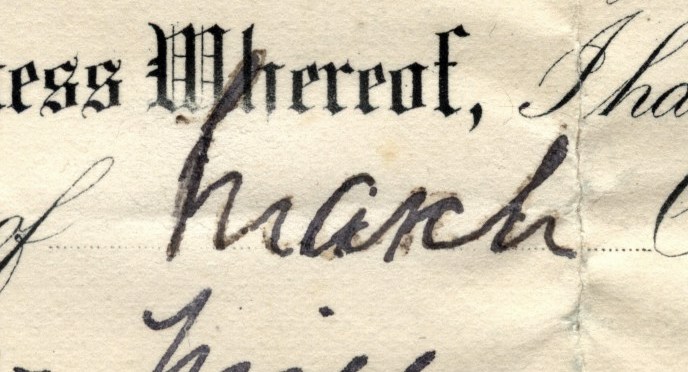

I can’t remember when I first held this up to the light.

Maybe before, but maybe not until after cousin Dick had pulled a copy of the municipal record from the City of New York, showing a different date.

Maybe before, but maybe not until after I had spent a year in European archives, carefully inspecting the erasures and corrections on thousand-year-old parchments by ultraviolet light.

At any rate it is readily apparent when you look at this certificate — a nice piece of engraving, but at some point folded up in someone’s pocket — that it has been tampered with:

Yes, they were married in June, not March. And yes, their first child, Eddie, was born the day after Christmas. The math isn’t hard.

(Continued)

Thursday, January 3, 2008

This is one of those amazing genealogical synergisms, and it has a moral: get your brick walls online.

My wife’s great-grandmother Mary (Nye) Scott (1882-1965) —

— came from an old Great-Migration family in Massachusetts, the Nyes. But her mother Cora (Continued)

Thursday, January 3, 2008

This corpulent—and presumably tailless—Manx pretender gives American interest in premodern genealogy a bad name. Michael Andrews-Reading on his dedicated website, and other posters on the Usenet group rec.heraldry, have already reviewed the pretensions of David Howe. Much of what has been unearthed—even from Howe’s own pen—suggests that a profit motive may lie behind the patently unconvincing claim of an abandoned title, the posting of an ungrammatical, logically incoherent, and legally meaningless notice in the London Gazette, and the diligent but hamhanded efforts to bend Wikipedia to his purpose of a free publicity machine. If this is not in fact the case, then Howe has an extraordinary combination of naïveté and stubbornness—far beyond the ordinary flush of self-importance that amateur genealogists (especially we Americans) often exhibit when we discover some royal descent in our trees. Either way it seems obvious from the newsmedia that Howe has energetically orchestrated publicity for his charade and one must wonder why.

What I cannot decide is which scenario—Howe the fraud or Howe the fool—makes American interest in premodern ancestry look worst? Either way I foresee that this episode will do no service to the community of people, within the US and abroad, who are curious about such things as descent from premodern notables, or the constitutional or cultural afterlives of feudalism. As Americans, of course, our constitution has given us the right to smugly ignore all distinctions between real aristocrats and fake ones, and as a consequence (well, as a consequence of that, and of the dumbing down of modern society) our media are notoriously inept at it. But many people (even some of us Americans) have the tools and the specialized knowledge to tell one from the other. Should we be obliged to stir to set the record straight for the rest of them? Perhaps. (takes pen in hand…)

Thursday, January 3, 2008

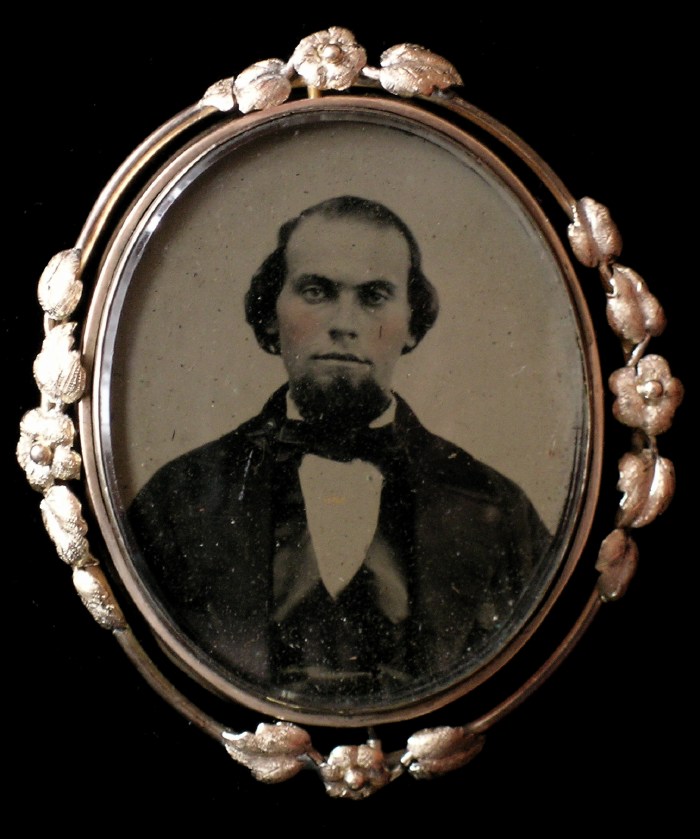

My wife’s family has handed down to us an interesting trio of early case photos, Daguerreotypes, all meticulously well identified. But from my father’s family in Kentucky have come a couple that alas remain unidentified! One is a hand-colored Ambrotype under glass in a typical mid-19th century case (photo after the jump). Another image is probably printed on paper, but set under glass into what appears to be a gold (or siver gilt) brooch: is this a mourning image? Can anyone identify its vintage from the photo (clothing style) and also from the brooch? Here he is, the mystery man:

Big lapels, satin waistcoat, straight tie. Is this about 1870 or so? Here (below the jump) is the Ambrotype: (Continued)