Here’s an interesting item: Count Rumford’s grant of arms from the English College of Arms:

This is from a fine on-line article on Count Rumford: Allen L. King, “Count Rumford, Sanborn Brown, and the Rumford Mosaic,” Dartmouth College Library Bulletin 35, New Series (1995).

I see this is one of those modern grants taking notice of an assumption of arms belonging to another family of the same name (and no proved connection), by granting a new coat with “such variations … as may distinguish [him] from others of the name”. The “ancient and respectable family of Thompson of the County of York,” on whose arms the grant was based, appears in the 1665-6 visitation of Yorkshire. As Matt Tompkins pointed out on rec.heraldry back in August 2006, the original family’s arms are, per fess Argent and Sable, a fess counter-embattled between three falcons, all counterchanged. Count Rumford’s arms differed from those in the substitution of a White Horse for the lower falcon.

Interesting to have the image of such a fine document granting arms to the man who, for a string of weird reasons, gave my street its fascinating defunct baking powder plant and gave our village its name.

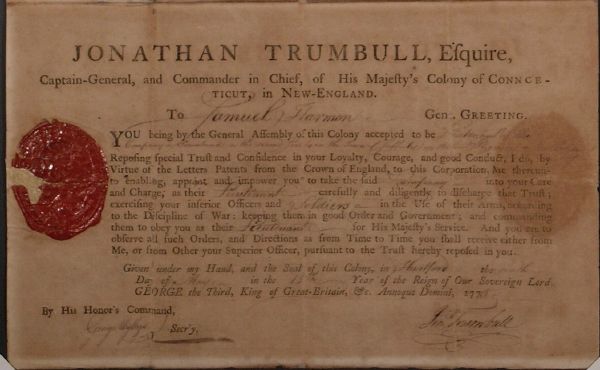

Just yesterday I got back from conservation and framing a commission in a colonial militia given to one of my wife’s ancestors at the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. The commission is typeset with blanks filled in by hand.

I give the whole text here [filled-in portions, as opposed to typeset boilerplate, are in brackets]: (Continued)

On another page, I have offered a genealogical definition of my children’s identity based on their seize quartiers, or their sixteen great-great-grandparents. Here is another form of such a definition. For persons predominantly or even partially descended from colonial lines in the United States, one shorthand for the ancestry is those people who are traditionally represented as the heads of their respective families in North America: the immigrants (usually men) who founded particular families bearing particular surnames. Both for New England and for the Mid-Atlantic and Southern regions, the early waves of immigration had specific collective identities, some of which are explored in such works as David Hackett Fisher, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (Oxford, 1989).

My children’s ancestry includes many who immigrated, or who appear to have immigrated, to the North American colonies or the United States after 1700—the most recent one, my wife’s mother’s mother’s father, came over about 1900—but the greatest likely overlap between them and other genealogists in this country is via common ancestors who came to the colonies before 1700: seventeenth-century immigrants. With many traceable New England lines via three out of four grandparents, our children have well over four hundred distinct seventeenth-century immigrant ancestors, if we take ‘immigrant ancestor’ to mean the first person in a particular agnate line to have come to this continent (thus eliminating doubling of father-son pairs who both came over, etc.). In addition to male founders of agnate lines, this list includes some women, of known surname, who appear to have immigrated without father or husband (or whose immigrant husband, if he came, remains unknown in colonial sources).

So as a sort of genealogical blueprint I have now drawn up a table of all ancestors known to have immigrated to (or be first known of their line in) the North American colonies before 1700. The table is available sorted in alphabetical order, date order (dated to apparent year of arrival), geographical order (sorted by state and town of principal residence), or pedigree order (based on the logical order of families in my children’s pedigree chart, following an order of precedence as if combining heraldic heirs).

I recently was thumbing through the book of UK Landmark Trust properties for short-term rent, and came across Calverley Old Hall, just outside Leeds, seat of the Calverleys who are ancestral to a cluster of American immigrants, including my ancestor William Wentworth of New Hampshire, who descends from Sir Walter Calverley (fl. 1415), husband of Elizabeth Markenfield. Most of the hall appears to date from one or two generations after this Sir Walter, however. One website mentions the later Sir Walter Calverley who murdered his two children (and tried to murder his wife) and was pressed to death in 1604.

The Landmark Trust book says that the rooms where the murders happened are not current bedrooms for renters—but how do they know? It might be fun to stay here while attending the annual medieval congress at Leeds some July (better than the dorms on campus). As Landmark Trust properties go, it’s not as pricey, as, say, Rosslyn Castle (home of the chapel famous for its carving and alleged Grail / Templar associations and now by that wretched Da Vinci Code).

How many houses ancestral to my family (say, 15th century and later) are available for paid lodging? This is the only one I’m aware of—so far.

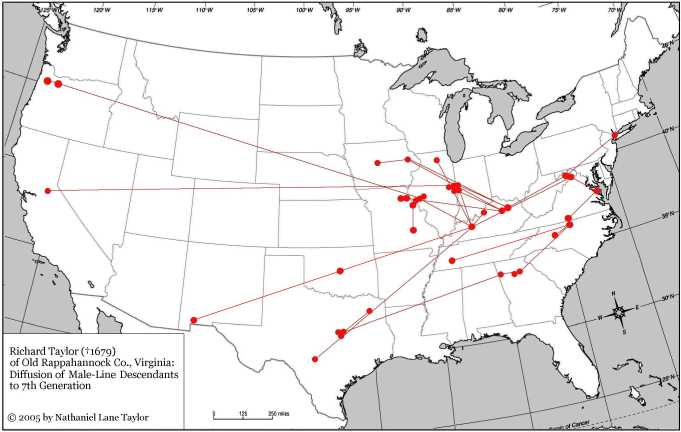

I finally did it today: I completed plotting, on an outline map of the continental United States, the places lived in by the first seven generations, in the male line, of my Taylor family, descendants of Richard Taylor, who died, testate, in 1679 in Old Rappahannock County on the Northern Neck of Virginia.

Looking at this family geographically in this way raises questions: is this family truly ‘Southern’? Why did no one settle between the Mississippi and the West Coast? The migration south to North Carolina opens up a whole separate path (North Carolina > Georgia > Texas) not discovered by me until recently (2002). What other unknown early branches may open up whole other geographic distributions?

It would be nice to see this as a time-series, perhaps (though this is beyond me) as an animated Flash picture, showing the migrations dynamically, and also showing the petering-out of earlier settlements (for example, I’m not sure whether any of this line stayed in Richmond County, Virginia—ground zero of the migration pattern—beyond say 1750).

But that, I suppose, is a project for another day.

The current version of my complete textual genealogy of this Taylor family is available as a pdf here.

When President George W. Bush used the word ‘Crusade’ in a speech about fighting terrorism on September 16, 2001, handlers and spin-doctors interjected quickly to disavow the loaded language. To speak of ‘Crusading’ was rightly perceived as antagonistic to the U.S. and global Muslim community—a group which at least some in the current U.S. administration would rather not alienate so decisively. But is ‘Crusading’ officially a dirty word? It may be helpful to quote the twentieth century’s most masterly and readable history of the Crusades, that by Sir Steven Runciman, which concludes with this judgment of the two centuries of massive military campaigns and colonization efforts by Western Europeans in the Holy Land:

The triumphs of the Crusade were the triumphs of faith. But faith without wisdom is a dangerous thing. By the inexorable laws of history the whole world pays for the crimes and follies of each of its citizens. In the long sequence of interaction and fusion between Orient and Occident out of which our civilization has grown, the Crusades were a tragic and destructive episode. The historian as he gazes back across the centuries at their gallant story must find his admiration overcast by sorrow at the witness that it bears to the limitations of human nature. There was so much courage and so little honour, so much devotion and so little understanding. High ideals were besmirched by cruelty and greed, enterprise and endurance by a blind and narrow self-righteousness; and the Holy War itself is nothing more than a long act of intolerance in the name of God, which is the sin against the Holy Ghost. [Sir Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, 3 vols. (Cambridge, 1951-4), 3:480 (“The Summing-Up”, conclusion).]

the home team (3d Crusade): from an English work of 1850

the home team (3d Crusade): from an English work of 1850Perhaps we owe the Crusaders a little more benefit of the doubt. (Continued)

One of the most pleasing of lineage societies has long been a fixture in my head, since as a child I watched endless ranks of minutemen file past on the Patriot’s Day parades each April 19 in Lexington, Massachusetts: the ‘Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company‘ of Massachusetts. Does ‘honorable’ necessarily belong with anything ancient, or if one hears it repeated in the title frequently enough, one believes it must be true? At any rate, this group wins both for its pleasing name (wearing its self-image in its very title) and for its ancient-ness, since being founded in 1637 it leads the order of precedence repeated among ‘lineage societies’—for those who care about such matters (I have more to say about the spurious age of some lineage societies elsewhere).

One thing I like about the ‘Ancient and Honorable’ is that one needn’t be a descendant to join: it is a fraternal organization, a reenactor’s group, and a civic group with a purpose which has un undeniably timely cachet in our current hawkish and defense-conscious regime. But it seems fun that there is a membership category for members ‘by right of descent’.

At any rate, this is one of the few ‘lineage societies’ I take some pleasure in contemplating, and, though I have no ‘Ancient and Honorable’ descents myself, maybe my son might be interested in being affiliated with things that go bang. Or my brother-in-law, who introduced me to the pleasures of spud-chucking. On a separate page I give their descents from some of the early artillery company leaders and members.

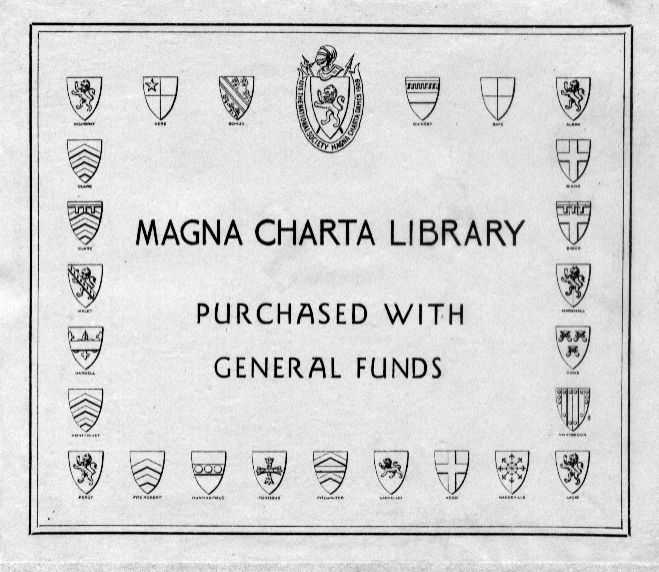

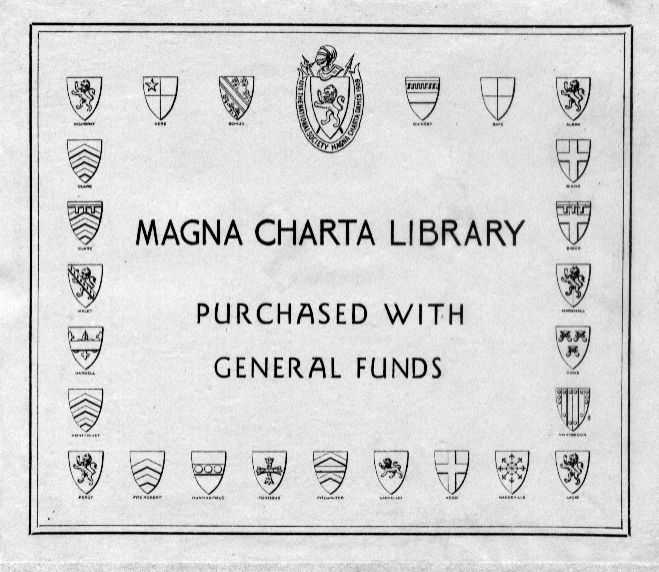

I broke down and had my copy of James Anderson’s Royal Genealogies (second printing, 1735) rebacked five years ago, but told the binder to retain the interesting bookplate which was there when I bought it: the bookplate of the ‘Magna Charta Library’ of the ‘National Society Magna Charta Dames’. It has the arms of the Dames at center top, surrounded by the arms borne by the 25 sureties chosen to watch over and harrass the king should he renege on his various concessions (see clause 63 of the charter of 1215, where the king tells them what they can do to him).

Indeed, for some time after buying the book (from a crazy but lovable Harvard Square bookman) I had pangs of guilt. Was it pilfered from the library of such an organization? No, I learned while talking with Lewis Neilson, the group’s chancellor: long ago the organization had a headquarters with research library, but this (and perhaps all other assets) had dissolved during a long dormancy. I gather that the current group is something of a recent reanimation, which would fit with the ebb, then revival of genealogy in the United States over the past two generations. The upshot was that I should feel no guilt about possessing this institutional vestige.

And perhaps I should not have felt too guilty anyhow. (Continued)

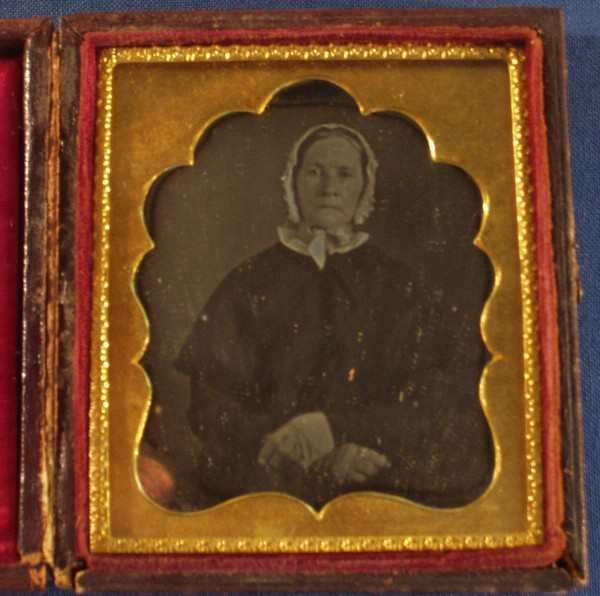

Three Daguerreotypes sat in the box with a make-up compact, a pill box, and little cut-glass dish, and two sandwich bags filled mostly with coins from Vichy France. The box was addressed to ‘Nathaniel Taylor, Historian’, and sent by my wife’s aunt.

I had never looked seriously into old cased photographs, though in my own family, along with about a century of memorabilia, there are a few miniatures in cases whose identities are no longer known (including an interesting mourning brooch, on which I will write later). With these Harmon family images, though, an assiduous great-great-aunt (Miss Hazel Harmon, quite a character) had kept them safe and labeled them, insuring their recognition into a third century.

Hannah (Beecher) Hotchkiss (1789-1854) [=Hannah6 Beecher (Benjamin5, Isaac4, John3, Isaac2-1)] had been widowed for some years when she sat for this photo, around 1850. She sits with a certain dourness (perhaps the product of a mixture of physical discomfort and skepticism of this odd fad). Her bonnet and gloves are proper and unadorned, and hark back to her eighteenth-century childhood as much as to appropriate going-out wear for the 1840s.

Her granddaughter’s father-in-law, James Hezron Harmon (1821-95) may have posed for this at the time of his wedding, 1844, in West Springfield, Massachusetts:

(Continued)

The pond in the heart of East Washington Village is stillness and motion as we walk (dog and I) over the dam. The dam and pond lie at the junction of Purling Beck and Woodward Brook, below Mount Lovewell. Below it is Beard’s Brook, a tributary of the Contocook, a tributary (I think, for here my map fails me) of the Merrimack.

The village of East Washington was founded around 1800 (Continued)