Two weeks ago I attended my first annual meeting of the American Society of Genealogists, meeting several of the other Fellows for the first time. Five days after coming home, I was in the dim, cavernous basement of the Registry of Deeds of Bristol County, Massachusetts, when someone approached me to fight over an index volume I was hoarding — and it turned out to be another Fellow, Fred Hart of North Guilford, Connecticut, whom I had met only the week before!

I was in Taunton on behalf of the Barrington Preservation Society, to research the chain of title for an eighteenth-century farmhouse on the other side of Hundred-Acre Cove, long held by members of the Allen family — not the Allin family who built my farmhouse in West Barrington. I had presumed the house belonged to a branch of descendants of John Allen of Swansea (d. 1683), an early Baptist follower of Rev. John Miles, whose first meeting-house lay next door to this Allen homestead. But instead, I was surprised by the revelation that the deeds for this Allen house led back not to the Swansea Baptist Allens, nor to the West Barrington Allins who built my own house, but to yet a third Allen family in the neighborhood, and moreover, to someone who was actually one of my own ancestors: Benjamin Allen (1652-1723), of Salisbury, then Rehoboth. I have lived in this corner of the Plymouth Colony for twelve years now, but only now feel like less of a newcomer, with this realization that an ancestor of mine settled in the same place 300 years ago! My next task is to locate his gravestone, in the Newman Cemetery where I walked my dog every day for years, without an inkling…

UPDATE, the morning after the election: After a blustery hour walking the Newman Cemetery, I went inside and checked the RI Historical Cemeteries Database Index. Benjamin Allen’s gravestone is not extant, nor for either of his wives: but I did find the group of stones for one of his children, David Allen (1707-1751), and his family. David, who is my ancestral half-uncle, lived on the parcel just north of the target of our house-research, which was his brother Joseph’s homestead. David’s land spanned four towns and two colonies, much to the consternation of anyone looking at his deeds! Here are David Allen and his wife Hannah:

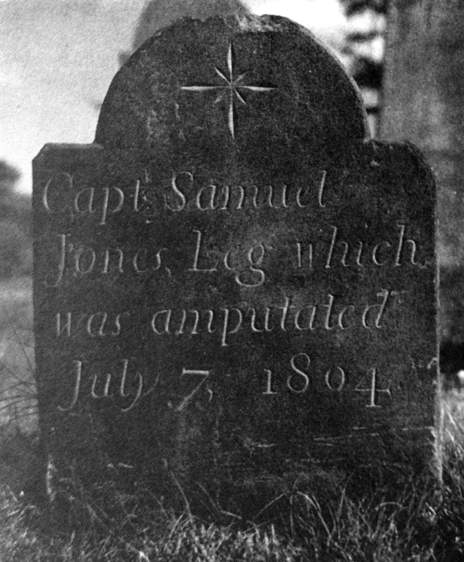

SECOND UPDATE, Friday of Election Week: Turns out that Benjamin Allen’s gravestone was extant into the early 20th century, though no longer. A 1932 alphabetized typescript of Newman Cemetery inscriptions (alas only abstracted, not preserving original inscriptions), lists him: “Allen, Benjamin, Sept. 30, 1723 in 71 yr.” (this is Marion Pearce Carter, “The Old Rehoboth Cemetery, ‘The Ring of the Town’, at East Providence, Rhode Island, Near Newman’s Church” [Attleboro, Mass.: the author, 1932], 58 pp., at RIHS Library), p. 1. I wonder if his is one of the many stones still standing, but with inscription completely obliterated? His may be the gravestone listed in the more careful transcription by Robert S. Trim (“Gravestone Records of Old Rehoboth, Massachusetts: Newman Cemetery,” compiled 1978/9, 230 pp. plus index, at p. 176), which records “Benjamin Allen . . . 1793 (Footstone): Headstone badly chipped and unreadable.” Since Trim notes that Mrs. Carter’s transcription did not include any stone for a Benjamin Allen in 1793, I wonder whether Trim misread 1723 for 1793? I will need to go find this myself. Trim’s transcription is done in some sort of perambulation order and lists this after a set of Butterworths (including Lieut. Noah Butterworth, d. 1736), and a Thomas Hawkins, “Born a slave in Kentucky”, d. 1863; and before Benjamin Rand, d. 1736 age 11; an undated fieldstone, and a stone for Jael wife of David Saben, d. 1726. So, maybe I can find this stone? I’ll try again on the weekend — supposed to be warm and sunny.